I'm still reading Frances's book. Slowly taking it apart, and all that. I admit it, I'm not all that quick-witted. It takes me a while to mull through a concept. Neurotic perhaps, and dull maybe, but that's who I am and what I've got to work with.

Something Frances said in his Saving Normal is bothering me a little bit. The preventative health care model is supposed to save lives. It's supposed to reduce the cost of treatment, but it often has the opposite effect according to him and others. There is empirical support for his view. Applying unneeded testing, and making those tests sensitive enough that they dragnet great swaths of humanity that doesn't suffer from disease, and never will is a costly endeavor. I think it's built on the social need to eradicate disease before it threatens the entire population. Obesity is one great big example (no pun intended) of this concept.

Most people will find a happy medium through exercise and diet, although there is a propensity for umami (fatty foods) and salt. These are obvious proclivities when evolution has designed a desire to keep and hold resources for later use. Obesity is that very drive taken to an extreme, but testing for obesity and aggressively treating it is causing a great deal of harm, and not just within the realm of medical treatment.

The current President of the APA, Dr. Bennett Johnson, called obesity the disease "that is going to bankrupt our country." How is this appropriate? Fat jokes are already a problem, ala bullying on schoolyards, and a thousand other places, including college campuses, and college classrooms, e.g. NYU prof Geoffrey Miller. Fat shaming is a problem that produces more pathology than it does healthy behaviors. So why this aggressive stance?

In the medical model, as I like to use my personal experiences from time to time, when my wife was unfortunately the owner of a fairly large ovarian cyst, we have staples, bands, and other treatments that aren't just aggressive but dangerous to combat this social ill. In the waiting room of the surgeon who (thankfully) removed the tumor, but also (irresponsibly) removed my wife's staples too early and thus caused a gaping, permanent scar and high probability of infection that could have proved fatal there were always women discussing how their gastric band had unintended consequences.

At one point do the risks outweigh the benefit, and aren't we far beyond that point in the US? What has the preventative model earned us on the front in the war against obesity? Our society seems focused on using inappropriately risky and often harmful methods instead of focusing on preventative measures that: a) are proven to work, b) are cheap to produce, and c) are tempered by reasonable expectations of outcomes.

The suggestion that the market will be there, and the bullying will be there, doesn't save my wife's surgeon, or Dr. Bennett Johnson from scrutiny. In so many areas, even in known cancer risks like smoking, aggressively treating the disease is causing more harm in anti-social attitudes, reaction formation, and prejudice than it is producing desirable results.

Using smoking as an example may be taking this argument too far, but it does make the point rather well. Much like the War On Drugs, and Nancy Reagan's "Just Say No" policy, and aggressive social campaign, it proved to be ineffective, costly, and produced the opposite outcome from the desired result. It was a joke. A laugh. A reason to smoke pot, not a reason against it.

Preventative strategies often mask deeper attitudes that direct behavior. Much like the war on drugs, and the war on smoking, I believe that there is a puritanical philosophy that drives the fear, and mistrust of liberal, democratic values. The authoritarian personality is a prime example of this notion of the Prodestant Ethic: that one treasure's one's body as a gift of god, works hard, offers fealty to authority, and does not question the nature of things or the consequences of the social order.

I think that preventative medicine is very much like giving an island to lepers and then letting them die off slowly. It reduces personal responsibility toward the collective, rationalizes a just world hypothesis, and feeds racist and prejudiced attitudes. Lest we forget the Iraq debacle, prevention is often practiced against ghost-like problems that match symptoms but do not match degrees and do not define prognosis.

And while we're discussing prognosis, let's consider psychopathy. There was a time when, in the disease model, that a disease was defined by it's prognosis meaning that what one could expect to occur defined a disease, or a disease was the product of it's outcome, not it's symptoms. Symptoms are the visible signs of disease but they are not, themselves the prognosis (or what will occur).

Considering the difference between secondary and primary psychopathy the formation of symptoms is not the only difference. The difference lies also in prognosis. Wherein secondary psychopathy one can expect a degree of self-healing given the right amount of time and circumstance, the same cannot be said of primary psychopathy, yet they are considered the same disease with merely like symptoms. This, I think, was the rationale behind adding antisocial personality disorder to the DSM. But by not including psychopathy in the DSM the differentiation never occurred even though, in this one case, we know that epigenetic expression of a particular gene, mono amide oxidase or MAOA is the cause.

Primary psychopathy and secondary psychopathy (APD) are different diseases because their prognosis, and their constructs are different even if they share some like symptoms. It seems lazy to me to not define it such when the tools are available, through even something as simple as an interview is capable of defining the difference between the two. Nevertheless, in APD, and Bipolar, among others, we have these overlaps of several different individuals with different diseases with different causes and different prognosis all lumped in the same boat together as one massive whole that society would really enjoy throwing down a completely different hole (now that was a pun).

This type of lumping is irresponsible where diagnosis defines treatment, and social stigma is very real even inside therapy sessions. Therapists are, after all, people, and subject to the same bias, and projective tendencies as the rest of us. These tendencies, are, however, forgotten. Chalked up to evidenced behaviors even though they exist inside the system of perceptions of the patient. Yes, therapists and doctors, you cannot help but act in a particular way once you've labeled your patient which demands certain characteristics from your client. Voila', we have yet another suggestible, but normal patient diagnosed and lumped in a box by yet another suggestible, but well trained therapist. And no one is paying attention.

Marvelous.

These two problems, although they seem distant, feed into each other to create bias. Frances's concept of diagnostic creep, and the problems inherent in preventative care have produced a situation that does not serve patients or normals. These situations serve several bottom lines. Not just big pharma.

Wednesday, June 26, 2013

Monday, June 24, 2013

What's the Point?

I've been playing around with the NPI because I'm concerned about a few things. I'm concerned because some of my behavior, according to a few of my acquaintances seems narcissistic. The problem is that when I'm honest in how I feel about the questions, I score consistently between either a 1 or a 4 depending on whether I'm feeling particularly grandiose. I even lied and garnered a score of 10.

How then, assuming that the NPI has external validity (if I got that right), am I narcissistic? I just don't get it. I do play up to people's expectations. I admit that. Being male one almost has to. Part of being a leader in any fashion is being thoughtful of the expectations of others and maintaining their opinion. Doing so ethically is defining one's actions by the consequences for not just oneself but others. I don't always get to be me, or do what would be best for me. That's part of life, and a natural part of being a leader.

As an example, I don't get to abuse my authority. I have to earn it, and keep on earning it day after day. But at the same time, those who are most likely to term me narcissistic, have more authority, and I do challenge them on particular points where I think they're wrong. I don't think challenging authority necessarily qualifies one as narcissistic whether or not the DSM defines it as a characteristic of a narcissistic personality. Where status is concerned, those who seek it are those who abuse it, and I'm well aware of that and I think they are too.

Nevertheless, I do think I haven't been genuinely myself. Not for a long time. I refuse to bow to whimsy, or what I consider to be ill-thought conclusions with more harmful consequences. Thinking about, "how do I fit inside these structures" never seems to happen. Perhaps those thoughts have already occurred, and yet, to ask a question once and deduce an answer isn't wise. Knowledge, and wisdom, come from asking the same questions over and over, and sometimes receiving different answers, then testing those answers both mentally and experimentally.

Why am I the only one that seems to see this? Because of my position, perhaps? That I have to prove it? Maybe. Those who are identified as ethical are more likely to abuse their authority. I can't remember the researchers who tested that hypothesis. I never should have sold my Social Psych text.

So, what's the point of reaching new heights when socialization structures replace my questioning with assurance that I know what I'm doing and stop questioning? I don't want to be the asshole who makes life more difficult for everyone, including me. (see productivity experimentation and theory) But is that who I must become? A narcissist? A fool? A fat bureaucrat sure of his own righteousness?

I think I'll stick to teasing out my own understanding.

How then, assuming that the NPI has external validity (if I got that right), am I narcissistic? I just don't get it. I do play up to people's expectations. I admit that. Being male one almost has to. Part of being a leader in any fashion is being thoughtful of the expectations of others and maintaining their opinion. Doing so ethically is defining one's actions by the consequences for not just oneself but others. I don't always get to be me, or do what would be best for me. That's part of life, and a natural part of being a leader.

As an example, I don't get to abuse my authority. I have to earn it, and keep on earning it day after day. But at the same time, those who are most likely to term me narcissistic, have more authority, and I do challenge them on particular points where I think they're wrong. I don't think challenging authority necessarily qualifies one as narcissistic whether or not the DSM defines it as a characteristic of a narcissistic personality. Where status is concerned, those who seek it are those who abuse it, and I'm well aware of that and I think they are too.

Nevertheless, I do think I haven't been genuinely myself. Not for a long time. I refuse to bow to whimsy, or what I consider to be ill-thought conclusions with more harmful consequences. Thinking about, "how do I fit inside these structures" never seems to happen. Perhaps those thoughts have already occurred, and yet, to ask a question once and deduce an answer isn't wise. Knowledge, and wisdom, come from asking the same questions over and over, and sometimes receiving different answers, then testing those answers both mentally and experimentally.

Why am I the only one that seems to see this? Because of my position, perhaps? That I have to prove it? Maybe. Those who are identified as ethical are more likely to abuse their authority. I can't remember the researchers who tested that hypothesis. I never should have sold my Social Psych text.

So, what's the point of reaching new heights when socialization structures replace my questioning with assurance that I know what I'm doing and stop questioning? I don't want to be the asshole who makes life more difficult for everyone, including me. (see productivity experimentation and theory) But is that who I must become? A narcissist? A fool? A fat bureaucrat sure of his own righteousness?

I think I'll stick to teasing out my own understanding.

And Another Thing: The Course of Disease

Why are there no books on the course of disease among the mentally ill? This would seem to me to be absolutely necessary, to establish the epidemiology of a particular disorder. So, why no interest in following the course of a disease to define an accurate prognosis?

Are we so sure of our affect that it is, by rights, disengaged from consequences as compared to the natural course of a disease? What does this say of our collective hubris? What does it say with regard to the consequences of our actions?

Can we say that what we're doing in the US in our push toward pathologizing, and treating larger and larger swaths of the public is both necessary, and has a desirable outcome. What does this say about the surge in plastic surgery? Is a consumerist demand the only test?

This seems more than foolish. This seems to lack any conversation with, or about, the consequences of societies actions, or the specific actions of health care professionals.

Where, in all of medical training, are these ideas?

Are we so sure of our affect that it is, by rights, disengaged from consequences as compared to the natural course of a disease? What does this say of our collective hubris? What does it say with regard to the consequences of our actions?

Can we say that what we're doing in the US in our push toward pathologizing, and treating larger and larger swaths of the public is both necessary, and has a desirable outcome. What does this say about the surge in plastic surgery? Is a consumerist demand the only test?

This seems more than foolish. This seems to lack any conversation with, or about, the consequences of societies actions, or the specific actions of health care professionals.

Where, in all of medical training, are these ideas?

Rule of Thirds

I've been reading (so what else is new) and finally ran across Hippocrates rule of thirds as explained in Frances's book, and, put simply, I'm vaguely concerned.

Why thirds?

As a short explanation of the concept: Hippocrates believed that prognosis was a vital skill that physicians had to develop. Part of prognosis was determining who could get value from care. He broke patients down into three categories: 1) those who would get better on their own, 2) those who could benefit from treatment, and 3) those who would never get better.

Presumably this set of standards was to prevent the loss of resources treating those who would eventually get better on their own, or those who would never get better. Ideally only those who could benefit from care would receive it. One of the questions that immediately springs to mind, among others, is "Who decides?"

In what way does bias feed into this game of thirds? It's really a simple question, but it means a great deal to people who suffer from disease, particularly mental disease. The bright lines between needing medical help, and too far gone to do anything for don't exist, including those between able to heal on one's own and needing medical or psychological attention. All these decisions, to make them more difficult, exist withing the social structures that we are all very much aware of.

What's to ensure a man of African descent will be treated with equal consideration? Or a woman? Or a man? Where does personal judgement conflict with an ethic of equality, particularly within a system so severely skewed by not just personal, but societal bias?

I have too many questions. What I don't have is answers, and maybe that's appropriate. Having an answer, a defined system of consequences offers assurances that what one is doing is right. It makes it easier to make decisions that affect people's lives, whether or not those systems of ethics truly reflect the world as it is.

Why thirds?

As a short explanation of the concept: Hippocrates believed that prognosis was a vital skill that physicians had to develop. Part of prognosis was determining who could get value from care. He broke patients down into three categories: 1) those who would get better on their own, 2) those who could benefit from treatment, and 3) those who would never get better.

Presumably this set of standards was to prevent the loss of resources treating those who would eventually get better on their own, or those who would never get better. Ideally only those who could benefit from care would receive it. One of the questions that immediately springs to mind, among others, is "Who decides?"

In what way does bias feed into this game of thirds? It's really a simple question, but it means a great deal to people who suffer from disease, particularly mental disease. The bright lines between needing medical help, and too far gone to do anything for don't exist, including those between able to heal on one's own and needing medical or psychological attention. All these decisions, to make them more difficult, exist withing the social structures that we are all very much aware of.

What's to ensure a man of African descent will be treated with equal consideration? Or a woman? Or a man? Where does personal judgement conflict with an ethic of equality, particularly within a system so severely skewed by not just personal, but societal bias?

I have too many questions. What I don't have is answers, and maybe that's appropriate. Having an answer, a defined system of consequences offers assurances that what one is doing is right. It makes it easier to make decisions that affect people's lives, whether or not those systems of ethics truly reflect the world as it is.

Sunday, June 23, 2013

Normal, Anyone?

I've been reading Allen Frances's new book, Saving Normal. In it I ran across a simplified discussion of something that's been bothering me for some time. During my investigation of psychology, even in my earliest understandings, there has always been the concentration on the pathological. Much like Seligman's appraisal in his TED talk, a focus on pathology leaves quite a bit to be desired, particularly when the definition of health, or even normal is undefined.

So, what is normal? That's one of the questions that Frances asks, as well as Seligman and notable others. Frances makes the point that the WHO definition is an impossible perfection. No one is without even the barest of hints of disease, maladaption, or strain. Such perfect contentment is fleeting if it ever does happen, and represents that which will ruin society as a whole.

This focus on perfect health, and personal responsibility for one's emotions is tantamount to enslavement, and I'll tell you why. Even when one's life circumstances are so dire, and unchangeable, the presumption is that the mind is free enough to soothe the pangs. Under this logic, victims of rape, torture, abuse, neglect are all not just victims, but victims of their own making. It's the just world hypothesis at work in its most insidious manner. Taken to its logical conclusion, no trauma rationalizes debility, therefore no debility is to be expected even in egregious circumstance.

The current trend of therapies toward fixing cognitive fallacies, though necessary, capitalize on precisely these belief structures that dangle out from the edges of trauma. Ellis was particularly ignoble in this regard, and in my mind so are his intellectual kin. Bowen's meta-systems theory is only slightly better. Without defining what's normal, and by extension what's to be expected inside the systems an individual represents, how can anyone hope to treat the individual swaddled by those same systems?

What's more, without defining health to a reasonable degree, analysts, therapists and researchers are swayed by cultural artifacts that direct not only their behavior, but the behavior, and lives of their clients as well. Perhaps Rogers was wrong about one thing (and probably more), that the "client" appellation would be good for the development of a relationship as a whole. It makes it easier for therapists and clients to join, this is true, but it also reduces the responsibility of the therapist in the situation. But then, with regard to Piff's recent studies on social class, perhaps Rogers was right, and didn't go far enough. Perhaps it's the "father knows best" attitude that drives a wedge between client and therapist and feeds a cavalier attitude toward what is essentially the "other."

CBT, and REBT does have value. I'm certainly not saying that it's worthless. Several studies have shown substantial effect sizes. However, it isn't the cure-all that some claim it to be, and it certainly isn't 16-week-savior it's often made out to be. Situational influences are very real, and commanding.

A person who works for minimum wage is never going to be wholly functional. And, it's very important to remember, perfect functionality is akin to psychopathology. There are some areas of life, and living, where it's perfectly reasonable, and desirable to be less than functional. In committing murder is only one extreme example.

Defining health, and defining normal, in my mind, should have been the first tasks of psychology instead of at, or near the last. But then, we simply don't pay attention to what's normal. It's part of what makes us what we are.

I still haven't figured it out. What the hell is normal?

So, what is normal? That's one of the questions that Frances asks, as well as Seligman and notable others. Frances makes the point that the WHO definition is an impossible perfection. No one is without even the barest of hints of disease, maladaption, or strain. Such perfect contentment is fleeting if it ever does happen, and represents that which will ruin society as a whole.

This focus on perfect health, and personal responsibility for one's emotions is tantamount to enslavement, and I'll tell you why. Even when one's life circumstances are so dire, and unchangeable, the presumption is that the mind is free enough to soothe the pangs. Under this logic, victims of rape, torture, abuse, neglect are all not just victims, but victims of their own making. It's the just world hypothesis at work in its most insidious manner. Taken to its logical conclusion, no trauma rationalizes debility, therefore no debility is to be expected even in egregious circumstance.

The current trend of therapies toward fixing cognitive fallacies, though necessary, capitalize on precisely these belief structures that dangle out from the edges of trauma. Ellis was particularly ignoble in this regard, and in my mind so are his intellectual kin. Bowen's meta-systems theory is only slightly better. Without defining what's normal, and by extension what's to be expected inside the systems an individual represents, how can anyone hope to treat the individual swaddled by those same systems?

What's more, without defining health to a reasonable degree, analysts, therapists and researchers are swayed by cultural artifacts that direct not only their behavior, but the behavior, and lives of their clients as well. Perhaps Rogers was wrong about one thing (and probably more), that the "client" appellation would be good for the development of a relationship as a whole. It makes it easier for therapists and clients to join, this is true, but it also reduces the responsibility of the therapist in the situation. But then, with regard to Piff's recent studies on social class, perhaps Rogers was right, and didn't go far enough. Perhaps it's the "father knows best" attitude that drives a wedge between client and therapist and feeds a cavalier attitude toward what is essentially the "other."

CBT, and REBT does have value. I'm certainly not saying that it's worthless. Several studies have shown substantial effect sizes. However, it isn't the cure-all that some claim it to be, and it certainly isn't 16-week-savior it's often made out to be. Situational influences are very real, and commanding.

A person who works for minimum wage is never going to be wholly functional. And, it's very important to remember, perfect functionality is akin to psychopathology. There are some areas of life, and living, where it's perfectly reasonable, and desirable to be less than functional. In committing murder is only one extreme example.

Defining health, and defining normal, in my mind, should have been the first tasks of psychology instead of at, or near the last. But then, we simply don't pay attention to what's normal. It's part of what makes us what we are.

I still haven't figured it out. What the hell is normal?

Wednesday, June 19, 2013

Dire Constraint and Work

In law, dire constraint represents the basic concept of a mugging when discussing a contract wherein the situation is the prime determinant of the validity of a contract. At this point we can start asking questions. One group of those questions has to discuss the limits of a reasonable expectation of rationality where work is concerned.

Work, as we know it today, is a little different from what it was in the past. At one time an employment contract included those unwritten rules of conduct that defined decent treatment of an individual employee. These unwritten rules were expanded on in writing through the FLSA (the Fair Labor Standards Act). But can we say that the FLSA went far enough?

Let's consider one situation where the FLSA may apply, and see if it does apply:

Let's take, for example, a theoretical woman entering the job market at a low wage employer. Without a work history, and without access to resources to afford, even in debt, the basic contributions to her own transportation to and from work. Let's say that she uses community resources in the form of loans to afford that transit to her position at a fixed place of business, perhaps a restaurant.

Let's say she performs beyond expectations in her position. Completes all required training at the place of business where she is employed. Let's then say that her employers require her to travel 50 miles one way to a training seminar that is only available for one day, which her employers notify her of that same day. She cannot afford the trip to the external training site as she makes minimum wage. All her wages go to surviving long enough to return to work. The employer nevertheless imposes the threat of terminating her employment if she does not attend the seminar.

FLSA only states that an employer is required to pay for time in training. It does not state that time in transit need be paid, nor does it provide for renumeration within such a small journey, nor does it suggest that she be compensated for travel expenses, nor does it require a time frame short enough to defer the actual cost. Nevertheless, the scenario presents a dire constraint. The figurative gun to her head is the loss of her low wage job. Their coercive tactics are unlawful even if they are not spelled out within the FLSA or other state or federal law.

There is a trend growing in this country. A derision of laborers, and an alignment of work-for-pay as a system of fealty. As if workers were feudal vassals, expected to defend the honor, and the profitability of the company for which they work or else.

At what point are we going to say, "This qualifies as dire constraint. The threat is real, and was communicated by an agent of the company. No such contract can be enforced and damages should be levied"?

Are there circumstances that require termination of contract? Yes, there obviously are. But to suggest that a person who works for minimum wage can effectively defend their own interests against a multinational conglomerate is ludicrous. Law should err on the side of the employee who has the least resources and can bring to bear the least able defense. Nevertheless, in this country might now makes right. If they can physically force an employee to do something, or do so by merely threatening their employment opportunity, then they may.

How is that in any way freedom? As if freedom to choose one's Machiavellian master is a freedom at all. It is a false choice and thus no contractual obligations can be enforced.

At what point did America become the corporate state? Was I asleep when corporate interests were handed a figurative gun and the permission to use it as they will? Was I gone when the law became something other than a system of negotiation to normalize relations between two parties?

Normalizing relations, in America, now means handing the criminals the keys to their cages and arming them with the tools to perform their crimes. No wonder rape is such a problem here. Exploitation, connivance, and coercion are part of our culture now.

It is a culture I do not like, and will always fight against to the best of my ability.

Work, as we know it today, is a little different from what it was in the past. At one time an employment contract included those unwritten rules of conduct that defined decent treatment of an individual employee. These unwritten rules were expanded on in writing through the FLSA (the Fair Labor Standards Act). But can we say that the FLSA went far enough?

Let's consider one situation where the FLSA may apply, and see if it does apply:

Let's take, for example, a theoretical woman entering the job market at a low wage employer. Without a work history, and without access to resources to afford, even in debt, the basic contributions to her own transportation to and from work. Let's say that she uses community resources in the form of loans to afford that transit to her position at a fixed place of business, perhaps a restaurant.

Let's say she performs beyond expectations in her position. Completes all required training at the place of business where she is employed. Let's then say that her employers require her to travel 50 miles one way to a training seminar that is only available for one day, which her employers notify her of that same day. She cannot afford the trip to the external training site as she makes minimum wage. All her wages go to surviving long enough to return to work. The employer nevertheless imposes the threat of terminating her employment if she does not attend the seminar.

FLSA only states that an employer is required to pay for time in training. It does not state that time in transit need be paid, nor does it provide for renumeration within such a small journey, nor does it suggest that she be compensated for travel expenses, nor does it require a time frame short enough to defer the actual cost. Nevertheless, the scenario presents a dire constraint. The figurative gun to her head is the loss of her low wage job. Their coercive tactics are unlawful even if they are not spelled out within the FLSA or other state or federal law.

There is a trend growing in this country. A derision of laborers, and an alignment of work-for-pay as a system of fealty. As if workers were feudal vassals, expected to defend the honor, and the profitability of the company for which they work or else.

At what point are we going to say, "This qualifies as dire constraint. The threat is real, and was communicated by an agent of the company. No such contract can be enforced and damages should be levied"?

Are there circumstances that require termination of contract? Yes, there obviously are. But to suggest that a person who works for minimum wage can effectively defend their own interests against a multinational conglomerate is ludicrous. Law should err on the side of the employee who has the least resources and can bring to bear the least able defense. Nevertheless, in this country might now makes right. If they can physically force an employee to do something, or do so by merely threatening their employment opportunity, then they may.

How is that in any way freedom? As if freedom to choose one's Machiavellian master is a freedom at all. It is a false choice and thus no contractual obligations can be enforced.

At what point did America become the corporate state? Was I asleep when corporate interests were handed a figurative gun and the permission to use it as they will? Was I gone when the law became something other than a system of negotiation to normalize relations between two parties?

Normalizing relations, in America, now means handing the criminals the keys to their cages and arming them with the tools to perform their crimes. No wonder rape is such a problem here. Exploitation, connivance, and coercion are part of our culture now.

It is a culture I do not like, and will always fight against to the best of my ability.

Hemispheric priming

I've been reading a couple of articles on hemispheric priming. One, through the BPS Digest, and the other a short section of The Neuroscience of Psychotherapy (I love Kindle editions. If only they were cheaper). Beyond the handedness thing, I find hemisphere priming intriguing, although I do have some questions.

Why do frightening faces integrate the hemispheres? Is the resulting stress response dangerous? Are temporal abnormalities like those in autism reintegrated with surrounding, and other-hemisphere systems by frightening stimuli? What are the possible effects of that much cortisol? Wouldn't the additional stress effects encourage apoptosis?

And what is the limit of stress effects anyway? These are all important questions to answer, I think. Particularly the last. I would expect this to be variable across the general population. Within autistics particularly, I would expect them to be more prone to stress effects.

Why do frightening faces integrate the hemispheres? Is the resulting stress response dangerous? Are temporal abnormalities like those in autism reintegrated with surrounding, and other-hemisphere systems by frightening stimuli? What are the possible effects of that much cortisol? Wouldn't the additional stress effects encourage apoptosis?

And what is the limit of stress effects anyway? These are all important questions to answer, I think. Particularly the last. I would expect this to be variable across the general population. Within autistics particularly, I would expect them to be more prone to stress effects.

Tuesday, June 18, 2013

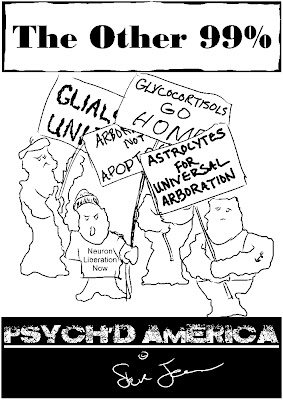

Neuron Liberation Now!

For too long neurons and glia have bowed to the powers of the cortisol elite! Take back your brain! SPIKE NOW!

Monday, June 17, 2013

The Situationist and other Internet Goodness

The Situationist is one of the oodles of pages of internet goodness that I never knew was there. I've been digging through a limited survey of their archives and papers, and am enjoying myself immensely. If I could captivate, in one quote, why I like this site, and this content, it would be:

"Try to be aware of what you bring to this article; be aware of how you read, why you are reading, and even that you're reading."

Handon, Jon. Yosifon, David (2004). "The Situation: an introduction to the situational character, critical realism, power economics, and deep capture."

So far it's well worth the read. I'm enjoying myself immensely. Ever since the fundamental attribution error was discussed in social psych (although I don't think that the name of this bias should include the word "error" because it defines an action that one can't prevent) I've been playing with it in the back of my mind. I've always thought that I over-empathized with people. It certainly does get me into trouble from time to time. However, defining the true authority of the situation on individual behaviors is a worthwhile task.

Questions like those presented by Handon and Yosifon are worth asking, and not just in the realm of law. The limits of individual responsibility, and individual change are inherently teasing; these limits produce a concept of a world where no behavior is unaffected, no matter how trivial. The naturalness and disposition of any individual is immediately suspect. This is broader than my view, but matches a longstanding hunch I've had about others.

"Try to be aware of what you bring to this article; be aware of how you read, why you are reading, and even that you're reading."

Handon, Jon. Yosifon, David (2004). "The Situation: an introduction to the situational character, critical realism, power economics, and deep capture."

So far it's well worth the read. I'm enjoying myself immensely. Ever since the fundamental attribution error was discussed in social psych (although I don't think that the name of this bias should include the word "error" because it defines an action that one can't prevent) I've been playing with it in the back of my mind. I've always thought that I over-empathized with people. It certainly does get me into trouble from time to time. However, defining the true authority of the situation on individual behaviors is a worthwhile task.

Questions like those presented by Handon and Yosifon are worth asking, and not just in the realm of law. The limits of individual responsibility, and individual change are inherently teasing; these limits produce a concept of a world where no behavior is unaffected, no matter how trivial. The naturalness and disposition of any individual is immediately suspect. This is broader than my view, but matches a longstanding hunch I've had about others.

Sunday, June 16, 2013

The Precariat and other Noms

Was surfing yesterday, you might remember the post that included an article by Dobson. In it he referenced a book, The Precariat that I've been reading since I found it. It's an interesting take on the shifts in labor behaviors over the last 20 years or so.

What I find particularly interesting is, as most of you don't know, my 39th birthday was last Thursday. I've been alive, and in the labor pool long enough to see some of these changes take effect. Granted on a much slower, and smaller scale. I was barely at my first job in the late 80's while some of what Guy Standing describes was starting to take place.

I thought that what I read of Standing's book dovetailed well with what I know of events simply from being alive, and what I've learned thus far about the social psychological processes of labor, value, and contributory meaning. How that meaning supports functionality. How that functionality supports social capital.

I've also been reading up on personality disorders, and it occurred to me that the recent rise in non-clinical narcissism might be a result of the precariousness of existence that Standing describes. Authority, self-sufficiency, entitlement, exhibitionism, vanity, superiority, exploitativeness are all possible affects of an environment that is highly inter-personally competitive, unstable, and unsupportive.

In a neoliberal, labor deregulatory environment, are these affects to be expected? Is there a risk of pathologizing individuals for the problems caused by social policy? In what way would this be a culture-bound psychological phenomenon rather than a pathology? And what do we make of, or attribute to the characteristic phenomenon of suicide that is increasing at an alarming rate? Has I/O Psych made a detrimental impact on the functioning of individuals in precarious situations?

I think these are important questions that need to be answered. I don't think the result of our combined limited understanding of what we know, or the result of our limited knowledge itself is considered enough.

Does this present an ethical dilemma of sorts? Is psychological research responsible for what people do with the knowledge gained? In what way?

What I find particularly interesting is, as most of you don't know, my 39th birthday was last Thursday. I've been alive, and in the labor pool long enough to see some of these changes take effect. Granted on a much slower, and smaller scale. I was barely at my first job in the late 80's while some of what Guy Standing describes was starting to take place.

I thought that what I read of Standing's book dovetailed well with what I know of events simply from being alive, and what I've learned thus far about the social psychological processes of labor, value, and contributory meaning. How that meaning supports functionality. How that functionality supports social capital.

I've also been reading up on personality disorders, and it occurred to me that the recent rise in non-clinical narcissism might be a result of the precariousness of existence that Standing describes. Authority, self-sufficiency, entitlement, exhibitionism, vanity, superiority, exploitativeness are all possible affects of an environment that is highly inter-personally competitive, unstable, and unsupportive.

In a neoliberal, labor deregulatory environment, are these affects to be expected? Is there a risk of pathologizing individuals for the problems caused by social policy? In what way would this be a culture-bound psychological phenomenon rather than a pathology? And what do we make of, or attribute to the characteristic phenomenon of suicide that is increasing at an alarming rate? Has I/O Psych made a detrimental impact on the functioning of individuals in precarious situations?

I think these are important questions that need to be answered. I don't think the result of our combined limited understanding of what we know, or the result of our limited knowledge itself is considered enough.

Does this present an ethical dilemma of sorts? Is psychological research responsible for what people do with the knowledge gained? In what way?

Saturday, June 15, 2013

mTurk and HIT Mores

Mechanical Turk is an interesting artifact that's become one of the tools in the top drawer of researchers. Initially started as Amazon's way of crowdsourcing tasks that required creativity, intelligence, and autonomy, it's become something much more than that.

While mTurk has successfully globalized a labor pool, it's also reduced compensation rates for time at task. Julian Dobson's recent article is worth a look, and describes something much more insidious than merely access to a larger pool of subjects. While Dobson quotes estimates from Panos Ipeirotus that between $10 and $150 million in business runs through the mTurk site, and into skilled workers, Dobson also suggests that this compensation is far below the level guaranteed by labor law.

Some tasks, Dobson notes, quite generously offer a whole $0.50 for a 150 word essay, while, in my own cursory review found such an outstanding deal quite rare. The average from what I saw was more along the lines of a 500 word essay for $0.02.

At some point there has to be a discussion about exploitation. Is it fair to say that exploitation isn't bad if it's done for a higher purpose? Or is that argument, itself, flawed? Is exploitation limited to actions forced on an individual? At what point can we say a behavior is elicited rather than a choice?

The ethical dilemma is often sidestepped in research. The potential gains seem to outweigh the risks, though the cost of exploiting a labor pool is quantifiable. Festinger's research on dissonance suggests only one possible cluster of outcomes. This notion is often forgotten, or summarily dismissed as not worth entertaining when considered against the potential gains.

Scientists need to face their own image in the mirror on this issue. Ethical guidelines are there for a reason, and little consideration is being paid to the possible affect research using exploitative tactics is having on the population, much less the example it sets for commercial interests.

The largest question, and the most poignant that I can muster, is why am I the one making this argument? As David Resnik of the NIH, says in his article, "a person who makes a decision in an ethical dilemma should be able to justify his or her decision to himself or herself, as well as colleagues, administrators, and other people who might be affected by the decision."

Again from Resnik, "When conducting research on human subjects, minimize harms and risks and maximize benefits; respect human dignity, privacy, and autonomy; take special precautions with vulnerable populations; and strive to distribute the benefits and burdens of research fairly." This point should be ruminated on in the larger academic community. With only a minimal view of research and how it treats its participants, even I'm uncomfortable with the recent trend towards mTurk as a source of research subjects, and not just because of the tragically low rate of compensation. Debriefing as well becomes problematic when subjects are not on hand.

Exploitative practices in finding, and funding research subjects are inherently dubious. This area of research needs to be at least discussed, if not debated in a larger forum. Compensation, just as deceit, needs to be discussed within the construct of its inherent ethical considerations. mTurk and like solutions should only be utilized as a method of last resort.

While mTurk has successfully globalized a labor pool, it's also reduced compensation rates for time at task. Julian Dobson's recent article is worth a look, and describes something much more insidious than merely access to a larger pool of subjects. While Dobson quotes estimates from Panos Ipeirotus that between $10 and $150 million in business runs through the mTurk site, and into skilled workers, Dobson also suggests that this compensation is far below the level guaranteed by labor law.

Some tasks, Dobson notes, quite generously offer a whole $0.50 for a 150 word essay, while, in my own cursory review found such an outstanding deal quite rare. The average from what I saw was more along the lines of a 500 word essay for $0.02.

At some point there has to be a discussion about exploitation. Is it fair to say that exploitation isn't bad if it's done for a higher purpose? Or is that argument, itself, flawed? Is exploitation limited to actions forced on an individual? At what point can we say a behavior is elicited rather than a choice?

The ethical dilemma is often sidestepped in research. The potential gains seem to outweigh the risks, though the cost of exploiting a labor pool is quantifiable. Festinger's research on dissonance suggests only one possible cluster of outcomes. This notion is often forgotten, or summarily dismissed as not worth entertaining when considered against the potential gains.

Scientists need to face their own image in the mirror on this issue. Ethical guidelines are there for a reason, and little consideration is being paid to the possible affect research using exploitative tactics is having on the population, much less the example it sets for commercial interests.

The largest question, and the most poignant that I can muster, is why am I the one making this argument? As David Resnik of the NIH, says in his article, "a person who makes a decision in an ethical dilemma should be able to justify his or her decision to himself or herself, as well as colleagues, administrators, and other people who might be affected by the decision."

Again from Resnik, "When conducting research on human subjects, minimize harms and risks and maximize benefits; respect human dignity, privacy, and autonomy; take special precautions with vulnerable populations; and strive to distribute the benefits and burdens of research fairly." This point should be ruminated on in the larger academic community. With only a minimal view of research and how it treats its participants, even I'm uncomfortable with the recent trend towards mTurk as a source of research subjects, and not just because of the tragically low rate of compensation. Debriefing as well becomes problematic when subjects are not on hand.

Exploitative practices in finding, and funding research subjects are inherently dubious. This area of research needs to be at least discussed, if not debated in a larger forum. Compensation, just as deceit, needs to be discussed within the construct of its inherent ethical considerations. mTurk and like solutions should only be utilized as a method of last resort.

Going All Meta

I was reading Rolf Zwaan's blog this morning on Klaus Fielder's recent presentation. I haven't yet had a chance to watch the presentation, but an interesting bit of debate has cropped up around the edges of the talk about validity: the notion that science should get weird.

Not to allude to a pop song, or Jon Hughes film from the 80's or anything so remarkably cool (yes, Weird Science, Anthony Micheal Hall, Ilan Mitchell-Smith, and Kelly LeBrock were awesome and I too wondered if I strapped a bra to my head and spent enough time at my Apple II+ complete with CAPS I could create a hot android out of whole cloth), but maybe more esoteric. Weirdness is the inescapable truth of science. At one point, all major discoveries were considered by the mainstream as incredibly weird, even (and especially) the notion of evolution, which should be particularly obvious considered the current of cultural revitalization that is such a part of modern American life.

But what I found most interesting about this specific post was a suggestion made in the comments by practiCal fMRI on knowing one's methods and how so often an attention to the details of the tools one has often drives creativity. In my last post, I discussed what it was like to build guitars, but what I didn't share was how I went about it, and why that process I followed made the struggle not only worth it, but invigorating. In the same way that the first Star Wars movie was the best of the lot from George Lucas (if we disagree here, I don't want to hear about it) the third guitar I ever built was my favorite.

It may not make much sense, but at the time I was crippled by monetary woes. Attendant to the needs and desires of the individual I was building it for (for free) I had to become resourceful rather than merely directing the resources required. It encouraged an intimate knowledge of the materials I had on hand. The focus was more about making the best of what the situation offered rather than using the best materials available on the market.

What I produced was inspiring, at least to me, and not just because of the limits imposed by my financial resources at the time. The care with which every action was taken was, I think, the determining factor, including a slightly adversarial process. The focus was merely giving my client what he wanted but in a way that would more than surprise him. I literally used scrap materials, experimented with binding materials that were exceptionally difficult to produce a product that was both one of a kind, and elegant. The only actual tonewood per se I'd used was the Engelmann Spruce top, a run off that took particular care to create the best reverberation that it was capable of.

The point I'm trying to make here is that not just knowing, but intimately knowing one's processes, one's tools, created the advantage, and the outcome that was desired in a way that the availability of resources never could. The situation offered the ability to produce a top-quality product out of less than ideal conditions. I never learned as much building any other guitar, and perhaps that's what's missing.

Opportunities to be resourceful. Rigid conditions that promote intimate knowledge of processes. Quasi-rational idealism. You know, weirdness.

Not to allude to a pop song, or Jon Hughes film from the 80's or anything so remarkably cool (yes, Weird Science, Anthony Micheal Hall, Ilan Mitchell-Smith, and Kelly LeBrock were awesome and I too wondered if I strapped a bra to my head and spent enough time at my Apple II+ complete with CAPS I could create a hot android out of whole cloth), but maybe more esoteric. Weirdness is the inescapable truth of science. At one point, all major discoveries were considered by the mainstream as incredibly weird, even (and especially) the notion of evolution, which should be particularly obvious considered the current of cultural revitalization that is such a part of modern American life.

But what I found most interesting about this specific post was a suggestion made in the comments by practiCal fMRI on knowing one's methods and how so often an attention to the details of the tools one has often drives creativity. In my last post, I discussed what it was like to build guitars, but what I didn't share was how I went about it, and why that process I followed made the struggle not only worth it, but invigorating. In the same way that the first Star Wars movie was the best of the lot from George Lucas (if we disagree here, I don't want to hear about it) the third guitar I ever built was my favorite.

It may not make much sense, but at the time I was crippled by monetary woes. Attendant to the needs and desires of the individual I was building it for (for free) I had to become resourceful rather than merely directing the resources required. It encouraged an intimate knowledge of the materials I had on hand. The focus was more about making the best of what the situation offered rather than using the best materials available on the market.

What I produced was inspiring, at least to me, and not just because of the limits imposed by my financial resources at the time. The care with which every action was taken was, I think, the determining factor, including a slightly adversarial process. The focus was merely giving my client what he wanted but in a way that would more than surprise him. I literally used scrap materials, experimented with binding materials that were exceptionally difficult to produce a product that was both one of a kind, and elegant. The only actual tonewood per se I'd used was the Engelmann Spruce top, a run off that took particular care to create the best reverberation that it was capable of.

The point I'm trying to make here is that not just knowing, but intimately knowing one's processes, one's tools, created the advantage, and the outcome that was desired in a way that the availability of resources never could. The situation offered the ability to produce a top-quality product out of less than ideal conditions. I never learned as much building any other guitar, and perhaps that's what's missing.

Opportunities to be resourceful. Rigid conditions that promote intimate knowledge of processes. Quasi-rational idealism. You know, weirdness.

Friday, June 14, 2013

More on Bad Science

I don't explain it very well. I suppose it's because I'm uncomfortable dealing with these issues. I'm not used to it. Perhaps, though, that's what makes some of that insight provided valuable. I don't know. People seem to me to be creatures of habit that slowly regress towards an established norm. That's not to say that people are lazy, or unethical, no, but rather that people have a tendency to feel sure in themselves that they're doing the right thing.

In a way it's a function of a reality check. Kind of like checking one's work when first learning a new skill. It's easy to consider one's work "good" on the first try, like when I was building guitars. I was surprised the first one didn't explode when I put strings on it for the first time. One slowly gets better at using the various tools in conjunction to perform a more complex task. And, like the guitars, they slowly get better overall.

But along the way the simple tasks get boring, and people tend towards impatience with tasks below their perceived skill level. They don't seem to be as valuable. Whether these routine tasks are simply unworthy of one's time, or too crude to be worth the effort to do them well is irrelevant. The fact is that the devil is indeed in the details. Simple, crude tasks are the bones of life. If one can find a way to enjoy those, then one can find a way to make a better mousetrap.

This concept may seem counter-intuitive. So much of education is built on knowing more, doing more, being more. Higher order problems, higher order solutions, higher order maths. Skills honed in a continuing pursuit of excellence. But the conquest of new knowledge is of no value without an understanding of the knowledge one already possesses.

In the same way that a thickness sander will do the same job as a hand plane faster, better, and more accurately, the hand plane requires patience, skill, and perseverance. It requires one constantly check one's work, and move forward slowly, calmly, and exactingly.

This notion, so akin to the guts of the often touted, and now lost, work ethic that used to be a part of American culture is what's missing. It was misunderstood as an amount of work, or a wealth of drive. "Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger," says Daft Punk, and rightly so. But the work ethic that's lost is not hard, is very much better, is in no way fast, and only its result could be said to be strong.

In science's effort to produce, a rigid adherence to the quality of the product has been lost. Much like the guitar market, social science is now made of plywood (prefab sheets slapped together from a cookie-cutter pattern zipped through by a speedy, needy, and anxious workforce) which is much easier to assemble, but sounds tinny, hollow, and without any soul.

The human qualities, one's body of work, and body of experience, have been lost in an effort to simplify the process and speed us to a result. Multiple publications are now expected before one even enters graduate school.

We're certainly kidding someone if we think this is how we develop quality research, but it's probably only ourselves.

In a way it's a function of a reality check. Kind of like checking one's work when first learning a new skill. It's easy to consider one's work "good" on the first try, like when I was building guitars. I was surprised the first one didn't explode when I put strings on it for the first time. One slowly gets better at using the various tools in conjunction to perform a more complex task. And, like the guitars, they slowly get better overall.

But along the way the simple tasks get boring, and people tend towards impatience with tasks below their perceived skill level. They don't seem to be as valuable. Whether these routine tasks are simply unworthy of one's time, or too crude to be worth the effort to do them well is irrelevant. The fact is that the devil is indeed in the details. Simple, crude tasks are the bones of life. If one can find a way to enjoy those, then one can find a way to make a better mousetrap.

This concept may seem counter-intuitive. So much of education is built on knowing more, doing more, being more. Higher order problems, higher order solutions, higher order maths. Skills honed in a continuing pursuit of excellence. But the conquest of new knowledge is of no value without an understanding of the knowledge one already possesses.

In the same way that a thickness sander will do the same job as a hand plane faster, better, and more accurately, the hand plane requires patience, skill, and perseverance. It requires one constantly check one's work, and move forward slowly, calmly, and exactingly.

This notion, so akin to the guts of the often touted, and now lost, work ethic that used to be a part of American culture is what's missing. It was misunderstood as an amount of work, or a wealth of drive. "Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger," says Daft Punk, and rightly so. But the work ethic that's lost is not hard, is very much better, is in no way fast, and only its result could be said to be strong.

In science's effort to produce, a rigid adherence to the quality of the product has been lost. Much like the guitar market, social science is now made of plywood (prefab sheets slapped together from a cookie-cutter pattern zipped through by a speedy, needy, and anxious workforce) which is much easier to assemble, but sounds tinny, hollow, and without any soul.

The human qualities, one's body of work, and body of experience, have been lost in an effort to simplify the process and speed us to a result. Multiple publications are now expected before one even enters graduate school.

We're certainly kidding someone if we think this is how we develop quality research, but it's probably only ourselves.

Thursday, June 13, 2013

Some Thoughts on Bad Science and p-hacking

As unfortunate as it is that I'm not part of the scientific community, I'm still a research consumer as a student. If that doesn't give me enough standing to weigh in with an opinion on this issue, then I'm not sure what would short of being a client, a member of society, or anyone on the planet that is affected by bad science. One giant point I'm trying to make here is that we're all affected by bad science, not just researchers, and not just research universities.

With that question settled (as far as I'm concerned), I think we have to consider how data is treated, particularly in this day and age. Data isn't just data, as much as this might surprise some. To offer a proof of this point, we can take two opposing theoretical stances, define our variables in relation to only one of those stances, work the same data for both theoretical scenarios and see if correlations exist.

This literally happens every day in social and psychological science, as Leslie John, Joe Simmons, Uri Simonsohn and others have suggested. And it's cheating, but one doesn't just cheat themselves. Everyone else gets to enjoy the ride too.

In order to understand why, one has to understand the process, from a top-down view of data collection. Some seem to believe it all starts with the research question. While this is an understandable error, it's still a mistake. The process starts much earlier, in the theoretical phase of investigation.

It's important to remember, a theory organizes existing data into testable questions that are falsifiable. The next step in devising a research plan is the actual hypothesis, but it's the next step after that where we really want to consider the consequences of using this data. After a hypothesis is defined, conceptualization of variables come into play, and this is where we'll find the source of the preventable mistakes made in modern science.

Defining a variable to test a hypothesis necessarily considers the accurate conception of the device(s) at work in the hypothesis. As an example we can consider the sexual acts of homo sapiens. Babies are the common result of the sexual act, but they are not the only result of the sexual act. If one wanted to know how much sex people were having, would the birth rate be a valid measure? No, it would not. The concept is different. Even though the birth rate suggests sexual activity, it does not define the breadth of it.

If, at the same time, we also collected the instance of venereal disease, age of the mother, and self-reports of extramarital sexual activity, considering that, as per the theory, babies only come from sex, but add the hypothesis that gonorrhea is produced exclusively from extramarital sex. So, the number of babies who's mothers also carried gonorrhea were produced by extramarital sex. At no time was the assumption of a positive proof mentioned of the original hypothesis which was necessary to prove the secondary hypothesis which has now been raised to the level of theory coupled with the hidden assumption of a moral philosophy that was never clearly represented, nor was the ludicrous hypothesis actually tested, but was, nevertheless, proven within statistical certainty, or enough so that we could at least shame them in public.

By the same notion, one wouldn't collect data on something as innocuous as what hair color the mothers had unless it was relevant to the presenting hypothesis only.

Finally, collecting random, irrelevant data is not merely an exercise in futility, it is a violation of the privacy of your subjects. Whether researchers are aware of it or not, they do have an affect on their research subjects. Suggesting that subjects are simply "black boxes" does not reduce professional responsibility. Schrodinger's cat is a lesson best learned before one introduces a corrosive into such a black box with a human subject inside.

Personally, I find the argument (I won't name where it came from) that the availability of finances necessitate the collection of a broad swath of data whenever possible appalling. Such sentiments are understandable, but nevertheless unethical, and lazy. The introduction of preventable error (mistakes, not error, and damn near fraud) into a system of analysis is unconscionable when subjects and clients lives depend on a researcher's methodology. Their trust, and the trust of your fellows should not be abused so lightly for so common and unworthy a cause.

Under the same reasoning it would be appropriate to run research projects outside the scrutiny of an ethics panel. In fact, that's precisely what researchers are doing when the collect data that is not relevant to their hypothesis, or use data collected under the umbrella of another project in their current work. Research review boards exist for a reason, and no researcher, no matter how trusted, righteous, or infallible, should be allowed to do as they will without any oversight. Historical lessons are painfully clear on this point. Even Goebbels had a Ph.D., was highly intelligent, and was considered a fine, upstanding member of his community.

With that question settled (as far as I'm concerned), I think we have to consider how data is treated, particularly in this day and age. Data isn't just data, as much as this might surprise some. To offer a proof of this point, we can take two opposing theoretical stances, define our variables in relation to only one of those stances, work the same data for both theoretical scenarios and see if correlations exist.

This literally happens every day in social and psychological science, as Leslie John, Joe Simmons, Uri Simonsohn and others have suggested. And it's cheating, but one doesn't just cheat themselves. Everyone else gets to enjoy the ride too.

In order to understand why, one has to understand the process, from a top-down view of data collection. Some seem to believe it all starts with the research question. While this is an understandable error, it's still a mistake. The process starts much earlier, in the theoretical phase of investigation.

It's important to remember, a theory organizes existing data into testable questions that are falsifiable. The next step in devising a research plan is the actual hypothesis, but it's the next step after that where we really want to consider the consequences of using this data. After a hypothesis is defined, conceptualization of variables come into play, and this is where we'll find the source of the preventable mistakes made in modern science.

Defining a variable to test a hypothesis necessarily considers the accurate conception of the device(s) at work in the hypothesis. As an example we can consider the sexual acts of homo sapiens. Babies are the common result of the sexual act, but they are not the only result of the sexual act. If one wanted to know how much sex people were having, would the birth rate be a valid measure? No, it would not. The concept is different. Even though the birth rate suggests sexual activity, it does not define the breadth of it.

If, at the same time, we also collected the instance of venereal disease, age of the mother, and self-reports of extramarital sexual activity, considering that, as per the theory, babies only come from sex, but add the hypothesis that gonorrhea is produced exclusively from extramarital sex. So, the number of babies who's mothers also carried gonorrhea were produced by extramarital sex. At no time was the assumption of a positive proof mentioned of the original hypothesis which was necessary to prove the secondary hypothesis which has now been raised to the level of theory coupled with the hidden assumption of a moral philosophy that was never clearly represented, nor was the ludicrous hypothesis actually tested, but was, nevertheless, proven within statistical certainty, or enough so that we could at least shame them in public.

By the same notion, one wouldn't collect data on something as innocuous as what hair color the mothers had unless it was relevant to the presenting hypothesis only.

Finally, collecting random, irrelevant data is not merely an exercise in futility, it is a violation of the privacy of your subjects. Whether researchers are aware of it or not, they do have an affect on their research subjects. Suggesting that subjects are simply "black boxes" does not reduce professional responsibility. Schrodinger's cat is a lesson best learned before one introduces a corrosive into such a black box with a human subject inside.

Personally, I find the argument (I won't name where it came from) that the availability of finances necessitate the collection of a broad swath of data whenever possible appalling. Such sentiments are understandable, but nevertheless unethical, and lazy. The introduction of preventable error (mistakes, not error, and damn near fraud) into a system of analysis is unconscionable when subjects and clients lives depend on a researcher's methodology. Their trust, and the trust of your fellows should not be abused so lightly for so common and unworthy a cause.

Under the same reasoning it would be appropriate to run research projects outside the scrutiny of an ethics panel. In fact, that's precisely what researchers are doing when the collect data that is not relevant to their hypothesis, or use data collected under the umbrella of another project in their current work. Research review boards exist for a reason, and no researcher, no matter how trusted, righteous, or infallible, should be allowed to do as they will without any oversight. Historical lessons are painfully clear on this point. Even Goebbels had a Ph.D., was highly intelligent, and was considered a fine, upstanding member of his community.

Wednesday, June 12, 2013

Hi.

Hi, and welcome to my repository of Psychology randomness. It's about as messy as inside my mind in here, so please, shove some books off a chair (but please stack them nicely) and sit down.

Psych humor is usually restricted to bad Freud jokes, and I see that as a problem. The larger community, myself as a student included, needs to be able to laugh at itself once in a while, and learn how to take criticism, again myself included. That's what this blog is for: a repository of the silly, and the social about psychology in general, and the people in it.

From statistical bloopers to albeit acidic 'toons, I'll try to find good content if you'll try to relax and not take it so personal. Hopefully we'll all have a good time, and learn to see a little bit of the funny.

Psych humor is usually restricted to bad Freud jokes, and I see that as a problem. The larger community, myself as a student included, needs to be able to laugh at itself once in a while, and learn how to take criticism, again myself included. That's what this blog is for: a repository of the silly, and the social about psychology in general, and the people in it.

From statistical bloopers to albeit acidic 'toons, I'll try to find good content if you'll try to relax and not take it so personal. Hopefully we'll all have a good time, and learn to see a little bit of the funny.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)